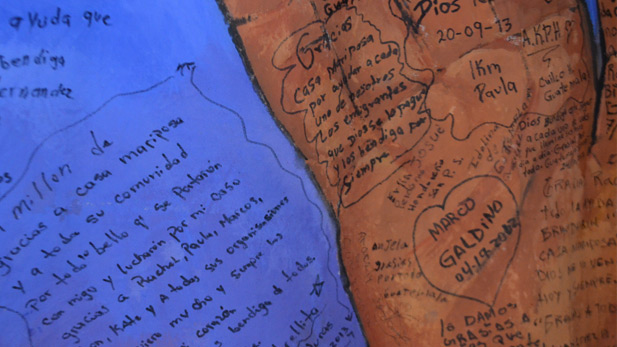

Galdino was released from a Florence immigration detention center in 2012 thanks to efforts by Tucson's Casa Mariposa. When he arrived to the Casa on that April day, Galdino signed his name on the wall.

Galdino was released from a Florence immigration detention center in 2012 thanks to efforts by Tucson's Casa Mariposa. When he arrived to the Casa on that April day, Galdino signed his name on the wall. Listen:

Marco Antonio Galdino is seeking asylum in the U.S., after what he says were years of physical and emotional abuse in his hometown of São Paulo, Brazil.

But he's not fleeing persecution for his political views or religious beliefs.

Galdino is gay.

"Despite Brazil calling itself an 'open country' for homosexuality, a carnival country, where everything is permitted, where sex is permitted, where liberalism is permitted...Brazil is one of the most homophobic countries in the world," he said in a fusion of Portuguese and Spanish. "It is a country with the highest number of homosexual killings in the world, a country where the violence against homosexuals is huge."

He fled Brazil in 1995, and currently lives in Tucson while he waits for a final decision on his case.

Galdino is among the between 4 percent and 10 percent of asylum seekers and refugees in the country who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, according to reports by the Rainbow Welcome Initiative, a Chicago agency, funded by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, focusing on LGBT refugees and asylum seekers.

The initiative was established in 2012 at the sight of increasing numbers of people pleading for asylum based on persecution for their sexual orientation or gender identity.

In Galdino's case, the abuse began at home.

"From all of the brothers, I was the most persecuted for being different, for being effeminate," he said. "So, my father, through beatings...he tried to teach me that that wasn't right. I don't know why I am the way that I am, but I am who I am and nothing will change that."

When asked about his mother, one particular memory came to his mind.

“I remember when I was 11 years old, I never forget these words, she said, ‘I prefer to cry you dead, see you in a casket with candles surrounding it, than to find out you are homosexual,’” Galdino recalled.

A lot of his childhood was spent in a basement. Galdino's father, who was in the Brazilian armed forces, would lock him in there for days, sometimes weeks. As a young boy, Galdino missed countless days of school, because his father didn't want anyone to notice his "femininity" and humiliate the family, he said.

At 18, he left home.

Galdino secretly moved in with his boyfriend at the time - a man from Uruguay named Andres. Galdino referred to him as the man who brought him out of the closet's darkness.

“I don’t know how my father found out where I was, he came one day…it was my birthday…I never forget, (my father) came to our home, and he took (Andres) outside, destroyed everything in our home, I still have scars from that time,” he said as he pulled his light brown trousers to reveal the marks he still has on his legs.

“He said, ‘You will never see this man again.’ And he took me out of there, he beat me until I lost consciousness, and he took me back home, where I was imprisoned for three or four months…My own father sodomized me. He was saying, ‘I will teach you a lesson, understand that you will never (be with men…)'" he said.

Once back at home, Galdino was shoved back into the basement he'd so often be in as a child. One restless night, however, the uncertainty of what happened to Andres drove Galdino to sneak out of the house, and head to the nearest police department to file a missing person's report. He said he also hoped to maybe find Andres in one of the cells.

"At first they (cops) treated me well...once they realized I was looking for my partner, the chief said, 'Oh you're another one trying to find your man,'" he said. "(The chief) ordered some guards to walk me to the back of the cells...I thought so I could look for Andres myself...one of the guards said, 'He's looking for his husband,' and he threw me in a cell...(in Brazil) jails are not the same as here, there are 30 or 40 men in one (big) cell..."

He said he was left in the cell for days, where he was repeatedly physically and sexually abused by other inmates. When he was released, Galdino was barely conscious. A couple of guards drove him to the hospital, and said they had found him on the streets, and that he had probably been robbed.

Galdino never saw Andres again. He said he assumes his father and the two men who accompanied him probably killed Andres.

During the conversation, he also looked back at the many other times he was brutally abused by Brazilian police, including being sodomized by a police officer during a gay club raid.

Global Persecution of LGBT People

Although Brazil is not among the more than 80 countries with anti-LGBT laws, statistics reveal persecution.

Brazil's oldest LGBT advocate group, Grupo Gay da Bahia, reported that in 2012, about 44 percent of all global cases of what the group refers to on their website as "lethal homophobia" occurred in Brazil. And in 2013, there were about 311 documented killings with genital mutilation, post-mortem burning and decapitation involved in the events.

Globally, about 76 countries mandate imprisonment of LGBT people, and seven - Yemen, Iran, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Somalia and Mauritania - punish homosexuality with death.

Most recently, Russia's anti-LGBT propaganda law has been in the headlines.

Natalia Polukhtin, a Moscow native and an immigration attorney in Phoenix, said she has more than a dozen LGBT asylum cases from people who escaped Russia and are now living in Arizona. She said she anticipates many more from those still eager to leave.

“Especially vulnerable right now are same-sex couples with children, because the law that exists in Russia prohibits the promotion of homosexuality before minors, and basically if you have children…you cannot avoid talking about your sexual orientation or hide it from your children,” Polukhtin said, sitting in her office on the third floor of the Global Practice Group building. “About two years ago, people started sending me emails, ‘Ok, you speak Russian, you can guide us through the legal process because we cannot survive in Russia anymore.”

During a visit to Russia prior to the Winter Olympics in Sochi, Polukhtin attended an asylum seminar and spoke with locals wanting to flee. Many of them were same-sex parents, who said social service workers would come to their homes, searching for any pretext to take away their kids, she said.

"Social services were openly telling them, 'Wait until the Olympics are over, we will come back to your apartment again,'" she said.

Similarly to Galdino’s experience in Brazil, Polukhtin said Russian police can also be at the forefront of the persecution. Such was the case of two of her clients who now live in Phoenix.

“…They were returning from the nightclub (in Russia) and they were attacked by a group of skinheads, a Neo-Nazi group, severely beaten, they ended up in the hospital,” Polukhtin said. “The next morning, when they were discharged from the hospital, they went to the police and filed a report about being attacked. What happened next is the police went to their apartment, searched it and started proceedings to take away their kids to teach them a lesson that they shouldn’t complain about it (the abuse).”

Polukhtin said she tries to speak with as many Russian LGBT asylum seekers. She said she gives them legal advice for free.

Abruptly Escaping Brazil

When Galdino fled in 1995, he wasn't aware he qualified for asylum based on the persecution he survived.

He got the green light for a six-month tourist visa, and moved to Salt Lake City, Utah. However, Galdino was only able to renew the visa a couple of times. For ten years, he lived in Salt Lake undocumented.

After an encounter with Salt Lake law enforcement, he was arrested and sent to an immigration detention center in Florence, Ariz., where he was held from 2005 until 2012.

Not knowing about asylum choices is a common trend among LGBT people fleeing persecution, according to Scott Portman, director of International Programs at the Heartland Alliance, a Chicago-based organization under the umbrella of the ORR, and father to the Rainbow Welcome Initiative.

“Firmly established in federal law and also in the appeals court…that sexual orientation is a ground for asylum, people can and will win asylum and get protection based on sexual orientation and gender identity…if they have a well-founded fear of persecution,” he said during a phone interview from Chicago. “A lot of people don’t access the system…they don’t know this, and a lot of people who are detained never see a lawyer, never have legal representation and don’t know what their rights are.”

Federal, Local Response to Persecution Based on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity

In 2011, the Obama administration issued a memorandum asking federal agencies to ensure there is equal protection for LGBT individuals throughout asylum and refugee agencies, Portman said. He explained this aims to fight global discrimination of LGBT people, as well as reinforce that sexual orientation and gender identity are grounds to file for asylum in the U.S.

Although the Refugee Act passed more than three decades ago, the inclusion of sexual orientation and gender identity into one of its categories is fairly recent.

“When the Refugee Act passed in 1980, there were five reasons for which an individual could resettle as refugee, and those five were: Experienced persecution of well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, political opinion or activity, nationality or membership in a social group,” said Natalie Brown, development director at Iskashitaa Refugee Network, a Tucson-based nonprofit offering services to refugees. “So, over the years, there have been court cases, federal circuit as well as immigration law court cases, they have really clarified something that was not universally agreed on, which was that, that last category does include identifying as LGBT.”

Brown has been studying webinars published by the Rainbow Welcome Initiative to incorporate the initiative's findings into the work Iskashitaa does with the refugee community. She's also been working with the LGBTQ Behavioral Health Coalition of Southern Arizona to ensure local refugee and asylum seeker programs are able to help LGBT people.

“The goal is that any person who is LGBT identified will not encounter barriers that are created by the social services organization,” said Davin Franklin-Hicks, a member of the coalition and the QI development administrator at La Frontera Arizona. “It is hard enough to get over the internal barriers, you shouldn’t have external barriers to speak your truth.”

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recognized a gap in the resettlement network's response to the LGBT asylum seeker and refugee population, and awarded the Heartland Alliance a grant to establish the Rainbow Welcome Initiative, a March 2012 press release from the Heartland Alliance explained.

The initiative provides resources for refugee programs' staff around the country, as well as LGBT refugees and asylees, with the goal to make refugee programs more LGBT friendly, and ensure asylum seekers are aware of their rights and asylum choices in the country.

"What distinguishes LGBT refugees from other refugees is the lack of support they often have when they arrive to the U.S.," said Daniel Weyl, the coordinator at Rainbow Welcome Initiative. "Often refugees who come based on their political affiliation, religious affiliation or their ethnicity, are more generally able to identify and locate other members of their communities who they can draw support from. Whereas LGBT refugees are often excluded and discriminated against by members of their ethnic or national communities."

Weyl, Portaman, Brown and Polukhtin all said they anticipate to see a spike of LGBT asylum seekers, in the coming years, from countries, such as Russia, where violence against LGBT people is high and no protection laws exist.

"It is very upsetting and disturbing to see the events both in Russia and elsewhere...that legislation is being passed denying basic, fundamental human rights of individuals just because of who they are and who they love," Weyl said. "Even in our country people are still discriminated against because of their sexual orientation and gender identity, but we see a shift in the U.S. in the LGBT civil rights movement."

Still Living with Uncertainty

After seven years in a Florence immigration detention center, Galdino said he never lost hope but slowly began to accept his "reality."

The conditions in detention and discrimination against LGBT detainees were detrimental, he said.

"I was tired of being in there," he said. "I always prayed to God, but that day I said, 'This is the last time I am praying. I cannot pray anymore. I am not asking you for anything else."

That same day, thanks to efforts by a Tucson group called Casa Mariposa, Galdino was freed on bail.

But today, he has another prayer: winning his asylum case.

Galdino first filed in 2005, but without any legal crutches, he lost. A deportation order emerged, and he has been appealing it since.

"In 2009 or 2008, I finally could get a lawyer," he said. "The lawyer saw my case, thought it was a good one, and he is still fighting my case. And we will see how it goes. It is still pending, and I don' know what is going to happen."

Galdino said he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, battling flashbacks from his past, while also coping with the possibility of, after close to 20 years, being deported to Brazil.

Despite having family in Brazil, he said he wouldn't have a place to live. Most of his friends are gone - as they also fled persecution for being homosexual.

"My future? I don't know," he said. "I live a constant personal trauma because in any moment there could be another deportation order, and I'd have to go back to jail and then be deported. I have my bags packed, my emergency luggage. If they call me, I have to go...but what worries me the most is my freedom, my safety because I don't know what could happen in Brazil..."

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.