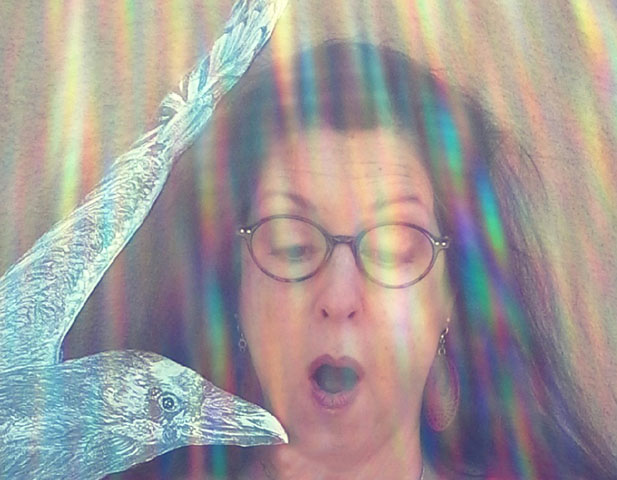

Artist and writer Beth Surdut listens to ravens and paddles with alligators in wild and scenic places. But she also knows that true adventure can be found just outside your window...

Listen:

Harris’ Hawks

© Beth Surdut 2015

Stuart Udall wrote, “Get to know the land and the messages it whispers to those willing to listen.”

I’m willing, but this is the city. No whispers here. The sound of cars and machinery is pretty constant, although never louder than the birdsong.

I heard noises on the patio, thought it was that large brassy ground squirrel that’d been hanging around, so I’d walked out to look.

Whoah!

Fierce, the Harris’ hawk glared at me with cantaloupe colored eyes.

It's unsettling to be that close to an angry raptor.

VIEW LARGER Harris' Hawk (in the Hood) by Beth Surdut, 2015

VIEW LARGER Harris' Hawk (in the Hood) by Beth Surdut, 2015

Hissed at me as it flew to a eucalyptus tree to scold me for all the neighboring animals to hear. (“Annnh, annnh, annh.”)

Big. Intent. Used to winning, I could tell.

Lush russet legs, substantial talons and a beak that could snatch the cat away.

The hawk returned the next afternoon, announcing as it flew overhead.

The cat, no fool, crouched by the kitchen door, watching through the screen.

A baby Anna’s hummingbird, old enough to flash crimson at it moved its head, young enough to be fluff, allowed me to stand near and watch it watch me.

The next morning, hawk flew in, perched on a telephone pole, dominating for only a moment before two mockingbirds give him what-for, screeching, scolding, pecking at his head and chasing him across the sky. His small but mighty escorts persisted, giving Hawk no chance to turn back.

Within a week, where there had been one Harris’ hawk, there were now four large birds, and I had their attention. It was around 7:30 in the morning, 88 degrees on its way to 107, and I was standing alongside the road by my house, holding aloft what I assumed was theirs—a dove, its head barely attached. I’d heard loud repetitive plaintive calls, different from the announcing voices-- two voices, maybe more, back and forth like echoes in a canyon. I spotted a twosome in a leafy eucalyptus, a third called from a backlit branch down the road, and a fourth on a utility pole-- a risky choice.

I dangled the surprisingly heavy kill by its feet, then set it down and moved away into the shade and waited. But no one swooped in as the heat of the day clung to me.

Harris’ hawks hunt in a group, flushing out the prey into the talons of the others. The alpha female might mate with two males and the offspring can stay around as long as three years. The four here are all large, but two often stay together and the other two are somewhat smaller.

Monsoon season has just started.

Late in the day, the hawks stand in the steady rain, wings spread like dark angels.

Lightning splits the sky as the raptors call to each other. Their calls bouncing around the darkening night.

Just above my neighbor’s house, 3 hawks huddle like Shakespeare’s witches amidst the metal coils and wires on top of a wood pole, intent on the kill the largest hawk is standing on and tearing apart. Must be something big—rabbit or ground squirrel--I see thick strands of guts hanging from the hawk’s beak.

The next day, with visions of electricity, water, and dead hawks in my head, I track down the number for the raptor protection program at Tucson Electric Power. In the early morning after that, I stand under the power poles around my house as Jim from TEP points out the protective coverings that have resulted in the raptor population being larger in the city than outside it. He explains that the coverings should keep the birds’ wings, with an average span of 40-47 inches, from touching the power sources on either side, causing the bird to act as a conduit. But what about the water? I ask, and he tells me that the mixture of birds and water can still mean death.

I’ve been in the city only a few months. My neighbors, who have been here for years, say, “The animals seem to find you.” I think not. I think I’m the intruder in animal territory.

Find more of Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

The Raven segment of Encyclopedia of Santa Fe and Northern New Mexico by Mark Cross is illustrated with The Reason Why along with her explanation of Raven calling her to the Southwest to draw and collect first person stories of interactions with this clever corvid and iconic spirit guide.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.