HoHum, the Great Horned Owl as a fledgling.

HoHum, the Great Horned Owl as a fledgling.

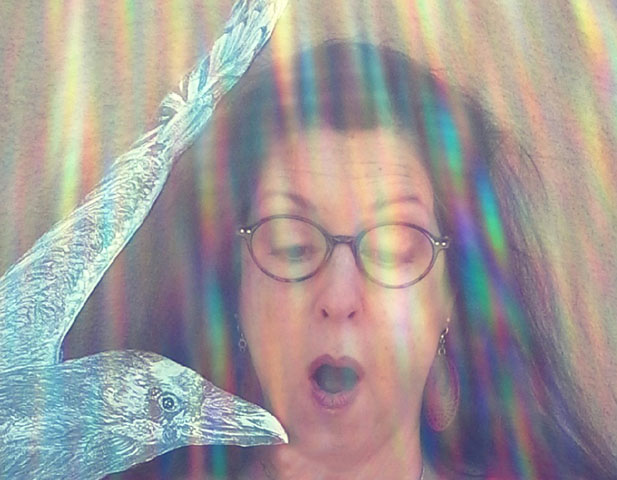

Author and wildlife illustrator Beth Surdut listens to ravens, and has paddled with alligators in wild and scenic places. This time, she introduces us to a local owl whose odd behavior sent her hunting for answers...

The Adventures of HoHum, the Great Horned Owl

© Beth Surdut 2017

From the moment I spotted the two Great Horned Owl chicks—their big-eyed fuzzy heads rising above their bulky nest-- the larger one, would watch me. If I bobbled my head, that chick would mimic my motion. If I changed the direction, so would the bird. I named her Bobble. HoHum, the smaller one, would always be looking off somewhere, not seeming focused on anything in particular.

VIEW LARGER The owl named Tristan is Iseult's mate for life.

VIEW LARGER The owl named Tristan is Iseult's mate for life. I’d witnessed the courtship of Bobble and HoHum’s parents. I named them Tristan and Iseult. Tristan is big, assured and impressive. From the top of his plumicorns—what appear to be horns, but are feathers-- to the points of his piercingly sharp talons, he is a model of his species. Except, according to statistics, he should actually be a she, because the female Great Horned Owl is usually larger than her mate. The male has a larger voice box and a deeper voice. Tristan not only has a deeper voice, but when the time came, he was not the one sitting on the nest. Funny how animals don’t read the manuals.

Let me orient you. There are three main trees in this story--sleeping tree, nesting tree, and hunting tree. The owls sometimes shift between them like a game of musical chairs.

Beth Surdut named this Great Horned Owl Iseult. Iseult is the mother of owls named Bobble & HoHum.

Beth Surdut named this Great Horned Owl Iseult. Iseult is the mother of owls named Bobble & HoHum. Once mated for life, Tristan and Iseult moved about a block away into an old hawk’s nest lodged high up in the fork of an Aleppo pine tree. Tristan brought food to Iseult during the month she sat on the eggs. After the babies were born, he continued to supply rodents, rabbits, birds and anything else he could catch. As the chicks grew into fledglings, Iseult began to leave them to go hunting. Tristan would sleep each day in the pine tree where the courtship began.

One day, I arrived to find that the nest was empty. I headed for Tristan’s usual roost, but he was gone.

At first, the tree seemed empty, so I looked for clues on the ground. A dove’s egg—unblemished-- lay where it had fallen on a bed of pine needles. Then I saw some fresh white owl splashes. They almost glow in the dark. I started scanning the branches and spotted a fledgling.

VIEW LARGER HoHum attempting to expel a pellet.

VIEW LARGER HoHum attempting to expel a pellet. I moved a bit, so did the owl's head as it followed me. I rotated my head, then nodded up and down—so did the owlet. I’d found Bobble!

Bobble seemed young to be alone, so with more scanning I found HoHum, about 8 feet away from his sibling, gazing off into wherever, but, as usual, didn’t look at me.

I kept looking and, farther up, at a distance, but within sight of her offspring, I recognized Iseult. She is the smallest parent I've seen so far.

Each evening, Iseult would fly out and land in the hunting tree within sight of the sleeping tree. Bobble would soon follow. Eventually, HoHum would too, sometimes first making a soft alarm like a chicken squawk, a baby sound, before he lofted. Then they would fly out into the darkening sky to hunt, returning to the hunting tree to eat.

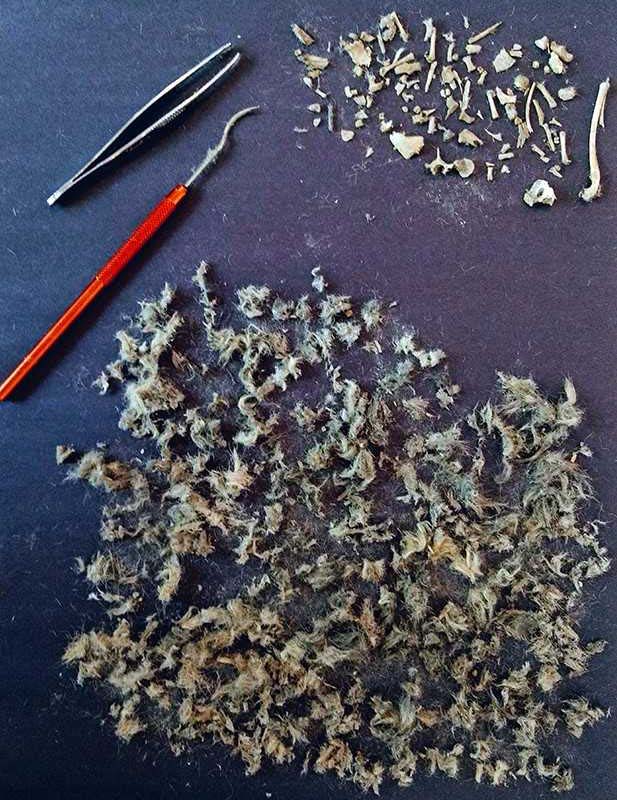

VIEW LARGER Owls, including HoHum, must expel pellets containing the indigestible parts of their prey before they can eat again, usually about every ten hours.

VIEW LARGER Owls, including HoHum, must expel pellets containing the indigestible parts of their prey before they can eat again, usually about every ten hours. Daily, I found headless corpses, sometimes two at a time, under the hunting tree—a rabbit on its side—oh those soft little feet, a dove with twisted wings, a packrat sprawled on its belly. Owls usually eat every part and let their systems separate out the indigestible bones, beaks, fur, and feathers. I admire that efficiency. If the death of one creature feeds another, so be it. Finding the corpses made me cranky-- that sloppiness, that waste of life.

With each cycle I’ve watched, there is a time when the owls leave the familiar trees. I continue to visit the same places, feeling bereft at the absence, but eventually the cycle starts again, and I find a solo owl. This time, I heard a soft babyish alarm cry, steady, repeating in the sleeping tree. I looked up, up, up and there was HoHum.

He sounded like a tired baby bird begging for food. The first time I found him alone, he continued to call as he flew to the hunting tree where he rocked to and fro like an unsteady tightrope walker. Then he lofted over to a more distant tree where he rocked again. He flew back to the hunting tree, and then returned to the sleeping tree. His cries grew softer, whimpering sounds, as night dropped its curtain on what I could see. I walked home, confused, having never heard this repetition of cries, nor witnessed this circling back at nightfall.

I visited HoHum almost every early evening before he flew out to hunt. This owl that had ignored me when his family was around, now cried softly as soon as he spotted me.

Unlike his younger days, he would watch me as I moved around under the tree where the monsoons exposed and scattered the contents of older pellets left by Tristan, Iseult, Bobble, and HoHum.

This miniature bone yard steamed with the earthy scents of rot that are usually masked by the aridness of the desert. Many of the pellets held only skulls.

VIEW LARGER One of Tristan the Great Horned Owl's dissected pellets.

VIEW LARGER One of Tristan the Great Horned Owl's dissected pellets. Amidst the damp and layered dead animal parts and plant matter, I found most of a freshly killed packrat on its belly, back legs pointing in opposite directions, head and shoulders gone. The corpse was misplaced, because owls usually eat after returning to the hunting tree with prey. When I left, I could hear HoHum’s voice all the way to my house.

I called my friend Amanda Remsburg, a certified bird rehabilitator in Houston. I was curious about the headless corpses.

“So he’s practicing. He’s learning how to hunt, and so he’s going to take all the opportunities that he can to practice. He might have brought it back to his sleeping tree thinking, hmmm, maybe I’ll want this for later.” - Amanda Remsburg, Houston-based wild bird rehabilitator

I walked out to check on HoHum, but couldn’t find any owls. Then I heard two voices—one higher than the other-- hooting at dusk. At first, the calls came from the eucalyptus trees across the street from my house where I knew a family of Harris’ hawks lived.

A few days ago, I heard hooting in the area of the hunting tree. It was almost dark when I went on my own hunting expedition, looking for signs under trees. There they were—fresh bright white splashes… two pellets, and a bird skull partially coated with chewed up feathers! Just a skull. The hooting started, and then a second voice. The foliage was so dense, I couldn’t see the owls until one and then the other flew to the next tree. They were both small compared to Tristan.

It looks like HoHum found the companion he needs. I bet he never talks to me again, and that’s the way it should be.

Visual storyteller Beth Surdut invites you to observe, with unbounded curiosity, the wild life that flies, crawls, and skitters along with us in our changing environment. From exotic orchids and poison dart frogs to local hawks and javelinas, Surdut illustrates her experiences with wild and cultivated nature by creating color-saturated silk paintings and detailed drawings accompanied by true stories.

You can find Surdut's drawings - and true stories about spirited critters - at listeningtoraven.com and surdutblogspot.com.

Beth Surdut's illustrated work Listening to Raven won the 2013 Tucson Festival of Books Literary Award for Non-Fiction. Elements of her raven clan have appeared in Orion Magazine, flown across the digitally looped Art Billboard Project in Albany, New York and roosted at the New York State Museum in an exhibition of international scientific illustrators.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.