Skiers descend Arapahoe Basin Ski Area in Colorado on May 4, 2025.

Skiers descend Arapahoe Basin Ski Area in Colorado on May 4, 2025.

If you took a look at a map of Rocky Mountain snow right now you would see a lot of red.

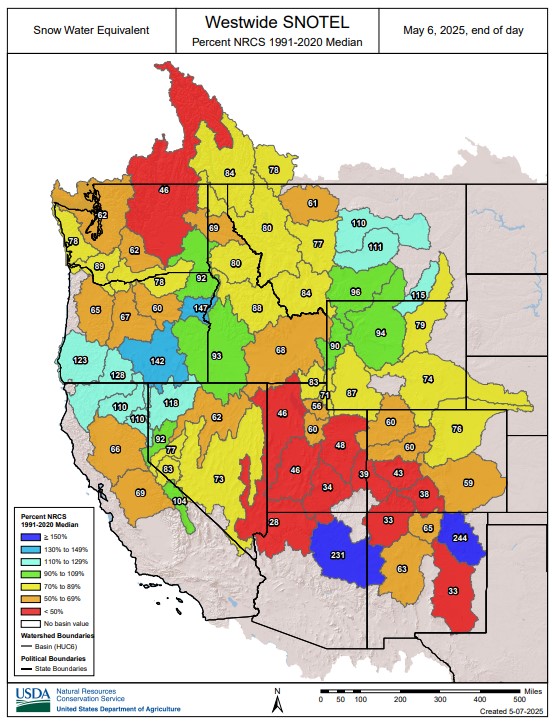

VIEW LARGER In this May 7, 2025 map, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico all show significantly below-average snow totals. Mountain snowmelt in those states accounts for the majority of the water in the Colorado River.

VIEW LARGER In this May 7, 2025 map, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico all show significantly below-average snow totals. Mountain snowmelt in those states accounts for the majority of the water in the Colorado River.

The mountains that feed the Colorado River with snowmelt are strikingly dry, with many ranges holding less than 50% of their average snow for this time of year. The low totals could spell trouble for the nation’s largest reservoirs, but those dry conditions don’t seem to be ringing alarm bells for Colorado River policymakers.

Inflows to Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir, are expected to be 55% of average this year, according to federal data released this week. If forecasts hold true, 2025 would see the third-lowest amount of water added to Lake Powell in the past decade.

“It’s looking like a pretty poor water supply and spring runoff season,” said Cody Moser, a hydrologist with the Colorado River Basin Forecast Center.

If Lake Powell drops too low, the reservoir would lose the ability to generate hydropower for about five million people across seven states. Much lower, and it could lose the ability to pass enough water downstream, where tens of millions of people depend on it.

Water sits low behind Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Arizona on November 2, 2022. Low water levels in Lake Powell could jeopardize the dam's ability to produce hydropower or pass water downstream.

Water sits low behind Glen Canyon Dam near Page, Arizona on November 2, 2022. Low water levels in Lake Powell could jeopardize the dam's ability to produce hydropower or pass water downstream.

Eric Balken, who watches Lake Powell closely as director of the nonprofit Glen Canyon Institute, said this year’s snow data is concerning, but it isn’t driving the same level of concern from policymakers and media outlets that emerged in previous dry years.

Balken said that this may be happening for two reasons.

First, it’s because negative outcomes might not be felt immediately. Lake Powell is unlikely to drop low enough to lose hydropower capabilities this summer, but the dry spring is making that more likely to happen in 2026. Second, it’s because water managers simply have bigger fish to fry.

The federal offices that manage Western water are in disarray amid layoffs and restructuring since Donald Trump returned to the White House. The Bureau of Reclamation, the top federal agency for Colorado River dams and reservoirs, is without a permanent commissioner.

All the while, state and federal policymakers are spending most of their time and attention on drawing up new water-sharing rules. The current rules expire in 2026. Talks between states have reached a standstill, and negotiators say they’re working toward a compromise.

“That chaos within the agencies, the broader negotiations happening on the Colorado River, all of these other factors, I think, are sort of drowning out the severity of the drought situation right now,” said Balken.

This year got off to a strong start for mountain snow, but took a dip during a dry spell that lasted from December through February. Snowmelt from Colorado accounts for about two-thirds of the water in Lake Powell. A portion of Western Colorado saw less than 15% of normal precipitation from December through April.

Scientists say these low snow years are the result of climate change, which is causing less snow to fall, and more of it to be soaked up by dry, thirsty soil before it has a chance to reach rivers and reservoirs. That has left the Colorado River in a dry trend going back more than two decades.

Balken said the climate reality is here to stay, and should spur the region’s leaders to rein in demand accordingly.

“Just because we've gotten used to it doesn't mean that it's not a problem,” he said. “We have to stay laser focused on what's happening on the Colorado River, because there are some very big problems that need to be addressed.”

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial coverage.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.