Raymond Mattia was shot and killed by Border Patrol agents outside his doorstep on the night of May 18, 2023.

Raymond Mattia was shot and killed by Border Patrol agents outside his doorstep on the night of May 18, 2023.

The day Annette Mattia’s brother died, about two years ago, she’d planned to celebrate his birthday. He’d turned 58 the day beforehand.

“I was going to go see him, but I got busy working on a fence, I didn't get to go and then it got late,” she said about her brother, Raymond Mattia. They're both Tohono O'odham tribal members and lived next door to each other in the Tohono O’odham community of Menager’s Dam. It’s a small village in the Tohono O’odham Nation that sits less than a mile from the U.S.-Mexico border, southwest of Tucson.

Annette says Raymond’s daughter was also planning to bring over a cake she’d made for her dad. Neither of them made it there that day.

“She didn't even get to give it to him,” Annette says. “So when his birthday does come up, you know, it's really sad for us, because we didn't even get to say goodbye to him.”

Raymond Mattia was shot and killed by Border Patrol agents outside his doorstep on the night of May 18, 2023.

Customs and Border Protection says the incident began when tribal police requested help responding to a 911 call.

An edited video released by the agency after the shooting shows body camera footage from some of the agents and audio from the initial police call. The dispatcher tells the Border Patrol operator about a dispute between an unnamed man and woman and gunshots she says may have come from the man’s house.

From left: Annette Mattia and her daughter Yvonne Nevarez at Annette's home in Menager's Dam.

From left: Annette Mattia and her daughter Yvonne Nevarez at Annette's home in Menager's Dam.The 23-minute video goes on to show several agents and a tribal police officer moving through brush and dry washes in a dark, dirt property. They eventually confront Mattia outside his small home and begin yelling commands.

“Put your hands up. Put that down. Put it down,” they say.

Mattia lobs a sheathed knife into the air and it lands near the police officer’s feet. Several officers and the police officer scream expletives at him, interchangeably asking him to take his hands out of his pockets, put his hands up, and get down on the ground.

You see Mattia’s hands go up, a flurry of more than two dozen gunshots rings out a second later, and he crumples to the ground.

The agents continue calling commands about securing a gun and bringing a medical kit. A cellphone is seen next to his body. They never find a weapon. He was unarmed at the time was killed.

Those moments are seared into Annette's brain. She heard everything from her house just down the road.

Annette Mattia was at home next door to her brother Raymond the night he died.

Annette Mattia was at home next door to her brother Raymond the night he died.“They stood in this clearing right here, and that’s where they shot Ray as he came out the doorway right here,” she said.

I met Annette on a windy day in front of Raymond’s house in Menager’s Dam. She’s lived in the village for more than two decades.

She’s adjusting a colorful Virgin Mary shrine and squat wooden cross marking the place where Raymond died in 2023. Nine bullet holes pierce through a thin wooden wall, and other parts of the house were boarded up.

She says she never heard the gunshots the 911 operator referenced. But, her brother told her about encountering migrants earlier that day. At first, she assumed the Border Patrol agents were responding to that. She called him after seeing agents rushing toward his home.

“He said, ‘alright, I’ll go talk to them.’ And I said ‘alright,’ and so I hung up, and two seconds later, that’s when I heard all the gunshots go off,” she said.

The family wasn’t able to get past the crime scene and see what had happened. It wasn’t until hours later that she was able to confirm it was Raymond who’d been shot.

“The coroner from Tucson did come and pick him up like seven hours later, and we said our goodbyes to him when he was in the body bag,” Annette said.

Changing policy

Still image from the body-worn camera footage from an officer at the scene of the fatal shooing of Raymond Mattia on May 18, 2023, at his home near Ajo, Arizona.

Still image from the body-worn camera footage from an officer at the scene of the fatal shooing of Raymond Mattia on May 18, 2023, at his home near Ajo, Arizona.Mattia was one of 44 people to die during Border Patrol incidents in 2023. That’s according to the advocacy group Southern Border Communities Coalition. The group has counted at least 335 fatal encounters with CBP since 2010.

The coalition's director, Lilian Serrano, says the majority were use of force incidents, like shootings and vehicle pursuits.

"The number one nationality [impacted] is Mexican, but it's immediately followed by U.S. citizen," Serrano said. "So we know that this level of violence by CBP agents and lack of accountability, while it impacts immigrants, it also impacts U.S. citizens."

No incident has ever led to a criminal conviction.

“In the 15 years that we’ve been tracking fatal encounters with CBP, not a single agent has ever been held responsible for the killing of an individual,” Serrano said.

But Mattia’s death is on camera. A Biden-era initiative now requires agents to wear body cameras and the agency to release footage of serious incidents. At least so far, the Trump administration appears to be continuing it — the last video release was in February.

Serrano says families still can’t access the unedited video. And details of federal investigations into incidents are still not released. Still, the program has ushered in some policy changes.

“We also know that we have a long way to go before we can actually say that these changes in policies have actually changed lives,” she said.

Department of Justice attorneys declined to pursue criminal charges against any of the agents who shot Mattia. The family filed a civil suit against the federal government and three agents whose names were obtained through a court order.

“The government and the agents have said that they did nothing wrong when they shot and killed an unarmed man in front of his home while he was compliant. And so, there’s going to be a trial, I expect, to resolve whether Ray’s killing was lawful,” said the family’s attorney, Ryan Stitt.

The suit is awaiting a hearing at a federal court in Tucson. It argues the named agents violated Mattia’s and his family’s constitutional rights, and also includes wrongful death and assault claims under the Federal Tort Claims Act.

Neither CBP nor the Department of Justice responded to requests for interviews for this story, or questions about the case. Court documents show the Justice Department attorneys are requesting to have various aspects of the case dismissed.

Menager's Dam runs right along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Menager's Dam runs right along the U.S.-Mexico border.Stitt says they’re hoping to obtain the full body camera footage. But the footage they do have is essential.

“From my perspective, it’s so important to require body worn cameras for law enforcement officers, because it provides an impartial and accurate representation of what transpired,” he said.

For Annette Mattia, Raymond’s sister, questions still linger about that night.

“If we didn’t do anything, or we didn’t say anything, this would have been gone a long time ago. The minute he was shot,” she said. “We want to tell his story and who he was, and what it meant to us. He was a big part of our lives and now he's no longer here because of this incident that … should have never happened.”

Mattia says she gets nervous, even today, seeing Border Patrol agents around Menager’s Dam.

“I get really bad anxiety, just to leave my house,” she said. “You know, one thing could lead to another … I'm here by myself, who am I gonna call?”

She says telling his story is one way she’s set out to honor her brother’s memory, especially ahead of the anniversary of his death.

“We still hear about how he knew so many people from all around and how he touched their lives, because that's the kind of person he was,” said Yvonne Nevarez, Annette’s daughter. The last time she saw her uncle was when they celebrated Mother’s Day weekend together.

“By the next weekend, he was gone,” Nevarez said. “We still have no closure, because they refused to hold anyone accountable or take responsibility for what happened.”

‘We are not surprised’

Protesters carry a large cloth banner with the names and faces of people killed during Border Patrol incidents.

Protesters carry a large cloth banner with the names and faces of people killed during Border Patrol incidents.The question of what happens when someone dies or gets hurt during an encounter with Customs and Border Protection isn’t a new one for border residents.

At a May Day protest in Tucson against the Trump administration’s immigration policies, Ana Maria Vazquez was one of three women who trailed behind the larger group carrying a cloth banner handpainted with a collection of faces.

“These people were killed by Border Patrol agents,” said Vazquez, who works with a group in Tucson called the Border Patrol Victim’s Network. “Some of them in Mexico, and some of them in the United States. The Mexican cases have all been closed.”

That includes the case of Jose Antonio Elena Rodriguez — an unarmed Mexican teenager who was fatally shot through the border fence in Nogales by a Border Patrol agent more than a decade ago. The agent, Lonny Swartz, has twice been acquitted of criminal charges since then, and the Supreme Court has ruled families can’t file civil suits for shootings that happen in Mexico.

“The thing for us is that we are not surprised what is happening, because we have been seeking justice for 12 years, and nothing,” Vazquez said.

But some things have been changing under Trump. Earlier this year, the administration began shuttering three different Homeland Security oversight offices that monitor everything from use-of-force policy to immigration detention standards and civil rights issues.

Employees of DHS’s Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Office, or CRCL, received notice the office was closing in March, according to initial reporting from Bloomberg. It’s a shift that impacts more than 100 federal workers, along with hundreds of active investigations.

Menager's Dam is a small community southwest of Tucson, in the Tohono O'odham Nation.

Menager's Dam is a small community southwest of Tucson, in the Tohono O'odham Nation.“You know, it was a mechanism for fixing problems, both small, like one person didn’t get their medication, and big, like use-of-force policies,” said Deborah Fleischaker, a former civil servant who spent more than a decade at the civil liberties office.

Fleischaker says the office has broad investigative authority that’s written into the Homeland Security Act — the 2002 law passed by Congress that established the Department of Homeland Security. Investigators look into a range of issues that stem from complaints submitted to them, news reports they read, or other problems they see within DHS — like whether traffic stops conducted by federal agencies are legal.

“How are they deciding to pull people over? And what is reasonable suspicion? Are they violating the 4th Amendment? It just sort of runs the gamut,” she said.

Even fully staffed, Fleischaker says the office can’t force change. But it can make recommendations and, it also produces reports about its findings.

The Trump administration has said the statutory responsibilities of the office would be shifted to other spheres within DHS. Fleischaker says she’s not sure how that would work without a dedicated office.

“You know, there’s a lot of complainants who had open investigations or recommendations that CRCL was working on with people, and those likely aren’t going to happen,” she said.

What’s next for reforms?

Family members of Tohono O’odham tribal member Raymond Mattia speak outside the Evo A. DeConcini Federal Courthouse in Tucson on Friday, Nov. 17, 2023.

Family members of Tohono O’odham tribal member Raymond Mattia speak outside the Evo A. DeConcini Federal Courthouse in Tucson on Friday, Nov. 17, 2023.CBP has seen changes over the last several years. In 2021, the Biden administration rolled out a pilot program requiring some Homeland Security personnel to wear body cameras while interacting with the public. The administration also revised certain policies around how Border Patrol agents are able to pursue vehicles and how use-of-force investigations are carried out.

Dan Herman is the senior director for democratic accountability at the Center for American Progress. He worked as an advisor to the CBP commissioner during the Biden administration.

“Many of these practices and ideas, particularly around body-worn cameras, were already happening during the first Trump administration, they just hadn’t been rolled out to a wider range, you know, at CBP,” he said.

Herman says they also have buy-in from agency personnel — since body camera footage could also protect an agent against allegations of misconduct. But, it’s still not clear how the changes will fare.

“Not having offices like CRCL makes it a lot more difficult for some of these reforms to be pushed through the agency,” said Serrano, the Southern Border Communities Coalition director. “There’s little oversight, and there are conversations about interpreting the laws differently to the benefit of the Trump administration’s agenda, to give more power to CBP agents.”

DHS didn’t answer questions about the future of body cameras for agents or what’s in store for the civil liberties office. But a spokesperson told Bloomberg the offices were adversaries that slow down immigration enforcement operations.

Serrano’s group is one of a pair that’s suing the federal government to get three offices closed in March to re-open. They argue the oversight mechanisms were created by Congress, and only Congress can remove them.

They’re asking the court to put a hold on the firings that are expected later this month. A hearing is expected next week.

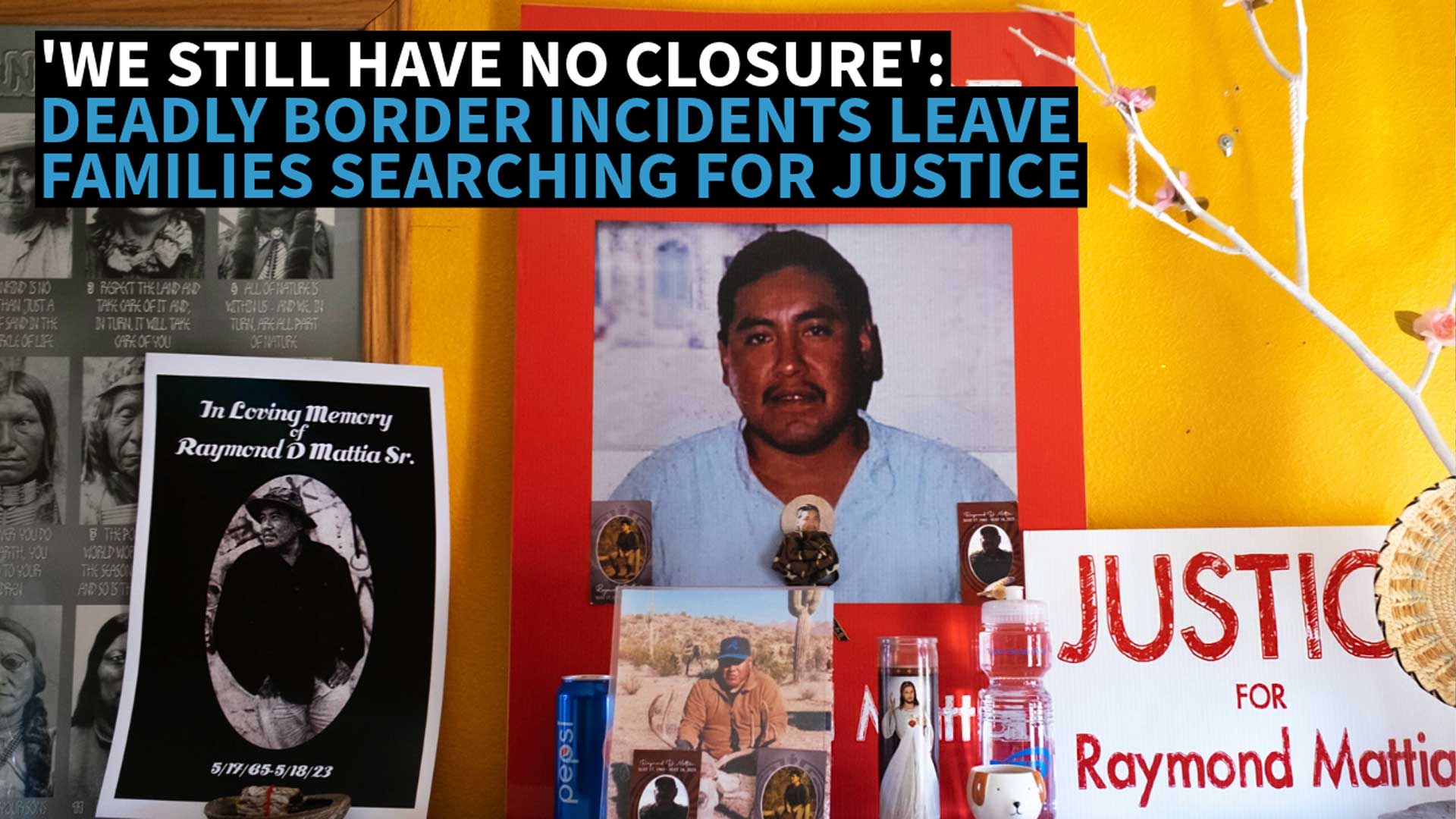

A small shrine is set up where Raymond Mattia died outside his home the night of May 18, 2023.

A small shrine is set up where Raymond Mattia died outside his home the night of May 18, 2023.

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.