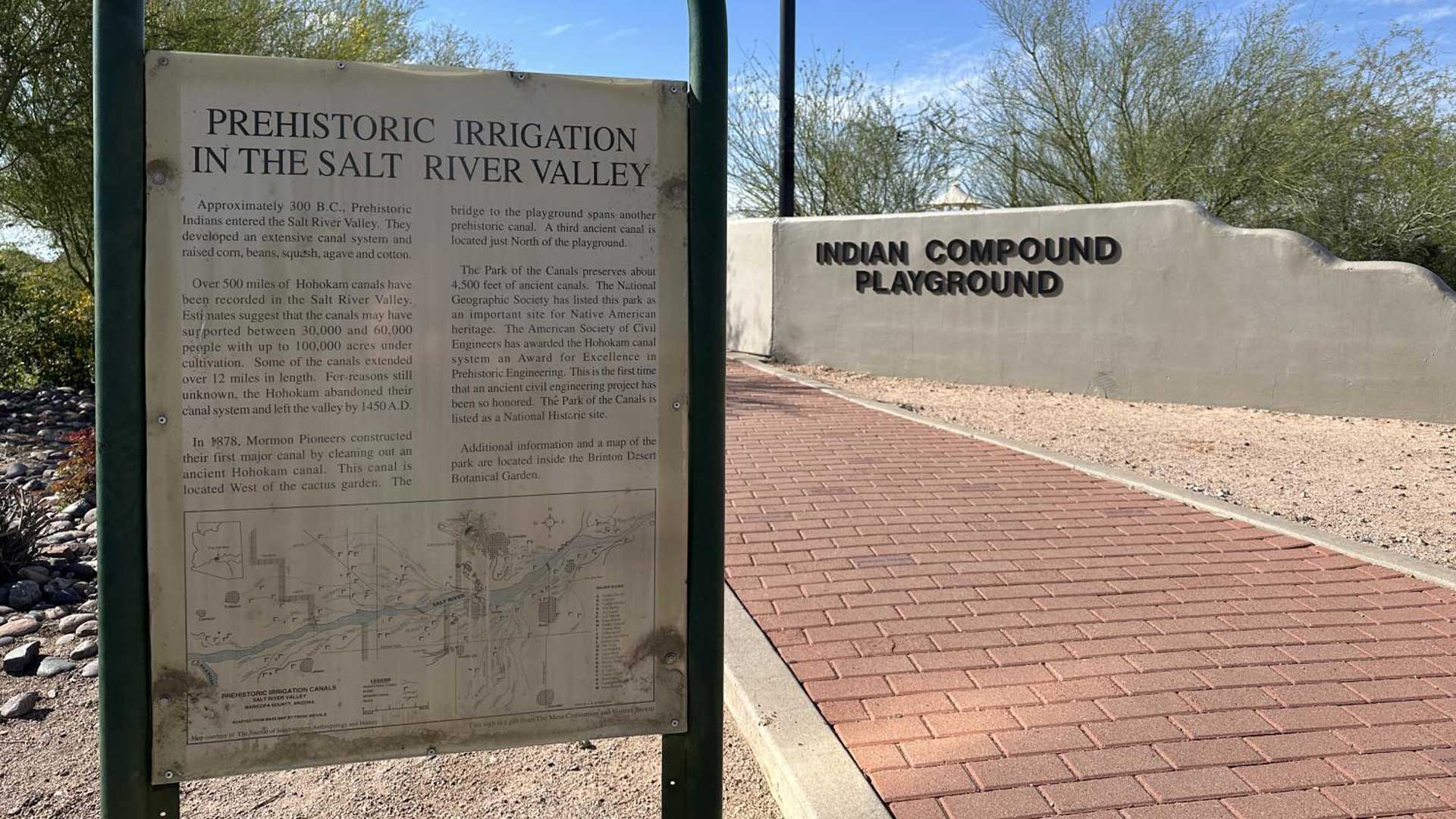

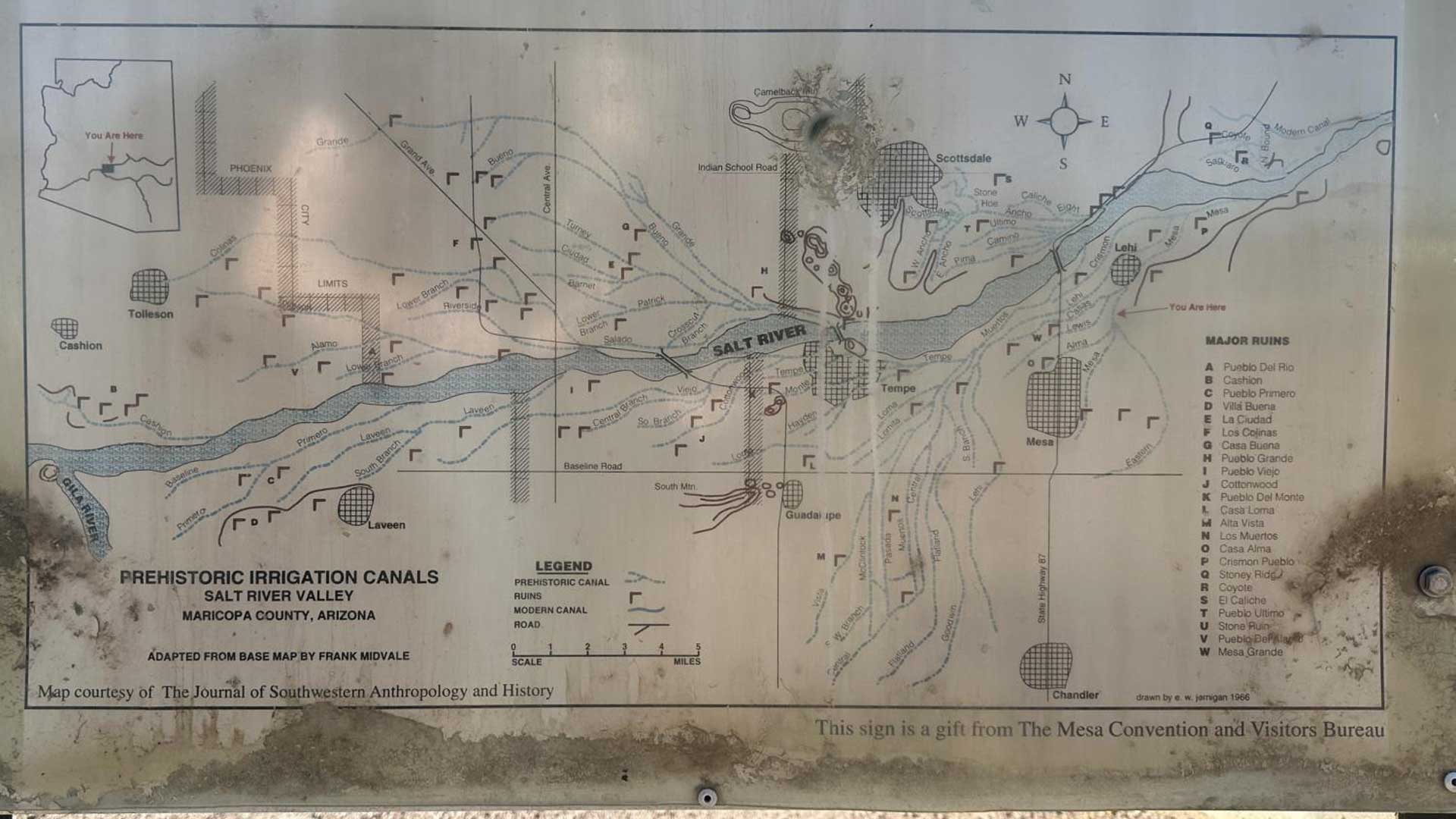

A marker at the Park of the Canals in Mesa shows a map of the ancient canal system dug by the ancestral Sonoran Desert people.

A marker at the Park of the Canals in Mesa shows a map of the ancient canal system dug by the ancestral Sonoran Desert people.

Just south of the intersection of North Horne and East McKellips Road in Mesa sits the Park of the Canals. It’s one of just a few places where you can still see remnants of canals dug by the ancestral Sonoran Desert people who occupied the Salt River Valley before the time of Christ.

Those ancient farmers have been referred to as the "Hohokam" but it’s not the name of a tribe or a people, and their O'Odham, Hopi, and Zuni descendants do not call them that.

Early archaeologists believe the culture developed in Mexico and moved into what is now Arizona. In order to flourish, they built an extensive canal system to bring water to villages and irrigate thousands of acres of agricultural fields.

At the Park of the Canals in Mesa, you can still see remnants of the ancient canals dug by the ancestral Sonoran Desert people before the time of Christ.

At the Park of the Canals in Mesa, you can still see remnants of the ancient canals dug by the ancestral Sonoran Desert people before the time of Christ.

Mark Tebeau is a public historian and professor at Arizona State University.

“There are places around the city where you can see the remnants,” Tebeau, “They kind of look just like abandoned ditches. They’re something you wouldn’t give a second thought to, right?” But those indents in the land once made it possible for about 60-100,000 people to survive in the early arid desert.

“They built canals in every place that it made sense to tap into the Salt River.”

Laurene Montero is the city archaeologist for Phoenix. She also works at the S’edav Va’aki Museum, another site dedicated to preserving some of those canals.

“The museum itself is on top of an archaeological site that is also a very important traditional, cultural place to the O’odham people because their ancestors were here and lived at this village site,” Montero said. Montero says the ancestral Sonoran Desert people worked with the natural landform to get water to move without any kind of power.

“They built the canals much as we’ve built them today with kind of the “V” shape and progressive narrowing of the channel to help keep the water moving at a rate that wouldn’t knock out the side walls, but also wouldn’t allow too much sedimentation to build up,” Montero said.

A marker at the Park of the Canals in Mesa shows a map of the ancient canal system dug by the ancestral Sonoran Desert people.

A marker at the Park of the Canals in Mesa shows a map of the ancient canal system dug by the ancestral Sonoran Desert people.

The system allowed them to grow corn, cotton, squash, and beans. Montero said it’s pretty remarkable considering they didn’t have draft animals or modern tools.

“They would’ve used sticks and stones for digging, and baskets for carting the dirt out, and yet some of these canals were — I mean, they were huge,” Montero said. “Some of them, from berm to berm, [were] like 80 feet across. And [they were] deep!”

If you add up the lengths of all the canals, it’s about 1,000 miles of prehistoric irrigation, but they weren’t all in use at the same time.

“Oftentimes they were built and they got flooded out and they cleaned them out, they reused them,” Montero said. “But sometimes they had to rebuild.”

The civilization drastically declined and many of the canals are believed to have been abandoned around 1450. Tebeau said no one knows exactly why but there are several possibilities.

“Whether it is the population grew beyond the ability of the canals to support it, whether it’s the drought itself changes the way the river is working for the community,” Tebeau said. “We don’t know exactly why it fails, but we know the failure of that canal is at the heart of the Hohokam collapse.”

Chris Caseldine is an ASU professor who’s worked on several projects related to irrigation through time. He said in the late 1800s, pioneers like Jack Swilling found the ancient canals and restored them to once again deliver water.

“There’s the adage that Phoenix was built on the ashes of a previous civilization,” Caseldine said. “It is correct that the ancestral O'Odham canals really enticed people to be in Arizona because the issue is not really too little water. We had a lot of water. It was just- do you have enough people to maintain the canals?” All these years later, some things haven’t changed.

“They’re not that dramatically different in size than our modern canals.” SRP archaeologist Dan Garcia said. In fact, the water still flows using the grade of the landscape to guide its path.

“I like to estimate that a big chunk of the early canal system that SRP still operates on behalf of the federal government that does follow the path and some of those are even the same canals as the ancient canals, just refurbished and modernized, Garcia said.

A biker rides down a path parallel to a modern canal in Mesa on April 8, 2024.

A biker rides down a path parallel to a modern canal in Mesa on April 8, 2024.

In many ways, the modern system that delivers water to more than 2.5 million people in the Valley is a monument to the state’s ancient ingenuity.

“We’d like people to know the history of these canals and how unique they are and how important they are, not only to us because, without the canals, there’d be no life in the Phoenix metropolitan area,” Garcia said, “but also the importance to the Native American communities that still live here. You know, their ancestors built these things and they’re still conveying water to the same places, along the same pathways as they were in ancient times.”

By submitting your comments, you hereby give AZPM the right to post your comments and potentially use them in any other form of media operated by this institution.